Though not yet six years old, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has accumulated a record of remarkable accomplishments. Despite uncompromising political opposition; widespread public misunderstanding; serious underfunding; numerous lawsuits, three of which have so far made it to the Supreme Court; and major technological failures at launch, the ACA has largely succeeded in its principal task—enrolling tens of millions of people in health insurance coverage. Indeed the period from 2010 to 2015 may be the most successful five years in the modern history of health policy.

The ACA has already achieved many significant accomplishments:

Despite these accomplishments, our health care system continues to face serious challenges, some traceable to flaws and weaknesses in the ACA. The ACA undertook from the beginning an ambitious reform agenda, but some of its approaches have turned out to be ineffective, poorly targeted, or not ambitious enough to address deeply rooted problems.

Many of the remaining challenges in health care reform reflect the inherent complexities and path-dependency of the American system and were beyond the reach of any politically feasible reform. Perhaps the most serious problem—which this report will address repeatedly—is the inadequacy of the ACA’s subsidies and regulatory structures to address the problems of low-income Americans, for whom merely meeting the costs of day-to-day essentials is a continuing challenge, and for whom even modest monthly insurance premiums and cost-sharing are often serious barriers to health coverage and care. 13

This report identifies problems and suggests potential solutions. Some solutions would require federal legislation. Others could be implemented by the administration, state law, or by private parties.

Some of our solutions are concrete and practical. Others are intended to provoke further thinking and debate. We have not precisely estimated costs and benefits, something that should be done before implementation. We understand that many of our proposals are not immediately politically viable. We believe it is important to think now about what should be done, and what the most important choices will be when political opportunities present themselves.

The first and second sections of our report describe steps to expand health care coverage and improve its affordability, particularly for low- and moderate-income Americans. The third section deals with improving the health care shopping experience for those who use health insurance marketplaces. The final section recommends improvements in the Medicaid program, which covers the lowest-income Americans.

In all, we propose nineteen steps that could help fix recognized flaws in the ACA as well as build on its accomplishments. Taken together, these proposals would further improve the access and affordability of health care under the ACA, create more robust provider networks, enhance competition among insurers, improve the consumer experience, and strengthen the Medicaid program. We understand that in the current political climate, improvements to the ACA that require congressional action are unlikely. Yet an administration committed to improving access could take some of the actions we recommend without new legislation, while other proposals could be implemented by the states, marketplace, or simply by insurers.

Fix the Family Glitch. Congress should clarify the legislative drafting ambiguity that led to the “family glitch,” or the White House should direct the Internal Revenue Service to interpret relevant sections of the Internal Revenue Code, so that working families are not excluded from marketplace tax credits. The result could allow up to 4.7 million people to gain access to subsidized health care coverage.

Reduce Complexity in the Tax Credit Program. The Internal Revenue Service should provide applicants to the ACA’s Advanced Premium Tax Credit program with clear and comprehensive explanation of how their credit was calculated as well as regular statements on applicant income so that burdensome tax credit reconciliations can be avoided. The result could help protect more of the approximately 4.8 million eligible taxpayers from receiving overpayments in advance premium tax credits.

Increase Credits for Moderate- and Middle-Income Families. Congress should consider either increasing the size and scope of the Advanced Premium Tax Credit program, or adding fixed-dollar, age-adjusted tax credits to the mix to improve access to affordable health insurance for moderate- to middle-income households. The result could dramatically expand coverage for families who currently receive little assistance under the ACA.

Reduce Cost-sharing and Out-of-Pocket Limits and Improve Minimum Employer Coverage Requirements. Congress should amend the ACA to expand eligibility for cost-sharing reduction payments and reduce out-of-pocket limits for moderate-income individuals or families. Congress or the administration should also improve minimum essential coverage and minimum value requirements to ensure that employees receive at least a minimum level of protection from employee coverage. These reforms could increase the affordability of coverage for millions of Americans.

Increase Use of Health Savings Accounts for Moderate-Income Americans. Congress should align the requirements of the ACA and of the health savings account program and consider offering subsidies for health savings accounts for moderate-income individuals and families. This could make health care more affordable for millions of moderate-income Americans.

Allow Use of Health Reimbursement Accounts to Purchase Health Insurance. Congress should amend the Internal Revenue Code to allow small employers to use health reimbursement accounts, with appropriate safeguards, to help the employees purchase health insurance. This could make health insurance more affordable for millions of people.

Incorporate Value-based Insurance Design to Support Coverage for High-Value Services. The ACA requires insurers to reimburse clinical preventive services without patient cost-sharing if these services receive an “A” or “B” rating from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. In similar fashion, expert bodies could require public and private insurers to cover high-value secondary prevention and disease management services without copayments or deductibles.

Improve State Regulation of Network and Formulary Adequacy. States should adopt legislation or amend existing legislation to ensure that insurer networks and formularies are adequate and nondiscriminatory. Control over networks is a legitimate approach to controlling health care costs and ensuring provider quality, but networks must be regulated to ensure that plan enrollees can access necessary care and are not discriminated against because of their medical conditions.

Improve Protection from Balance Billing. States should adopt legislation to protect network plan enrollees from balance billing when they access care in emergencies or through network providers. This is necessary to ensure that network plan enrollees are not burdened by crippling medical bills when they have not intentionally sought care out of network.

Actively Guide Consumers in Coverage Selection. The marketplaces should provide better tools, and personal assistance, to consumers to select plans. This could help ensure that consumers enroll in the plans best suited to their needs and resources.

Improve Network and Formulary Transparency. The marketplaces and state regulators should demand greater network and formulary transparency from insurers and deploy tools to help consumers better understand the networks and formularies available to them. This could help ensure access to appropriate care and continuity of care for consumers.

Standardize Insurance Products. Marketplaces should standardize products their insurers offer. This would facilitate and improve not only consumer choice but also insurer competition.

Have the Federal Government Permanently Assume the Entire Cost of the Medicaid Expansion Population. Congress should make permanent the 100 percent federal match for the adult Medicaid expansion population. This could encourage states to expand Medicaid coverage and protect the expansion population from future state budget-based cutbacks.

Constrain 1115 Waivers. Section 1115 waivers have proven an effective tool to permit the administration to accommodate the concerns of states reluctant to expand Medicaid. The administration needs to take care, however, that 1115 waivers are not used to undermine basic protections of the Medicaid program or to discourage enrollment.

Eliminate Medicaid Estate Recoveries from the Expansion Population. Congress or the states should prohibit estate recoveries from the expansion population. Individuals should not be discouraged from seeking the medical help they need for fear that, once they die, their beneficiaries may have to pay for the health care they received.

Improve Medicaid Payment Rates. The Department of Health and Human Services and the states should take action to ensure that Medicaid payment rates are sufficient to ensure adequate provider participation. Medicaid beneficiaries need not only a guarantee of coverage but also of actual access to available providers.

Ensure a Judicially Enforceable Right to Adequate Access to Medicaid Providers and to Adequate Medicaid Payment Rates. Recent court decisions have undermined the long-standing right of beneficiaries and providers to sue in federal court to ensure state compliance with federal Medicaid requirements. Congress should clarify continuing rights of access to federal court for Medicaid beneficiaries and providers to ensure that beneficiaries enjoy the access to care guaranteed them by federal law.

Reconsider a “Public Option” Early Medicare Coverage within Health Insurance Marketplaces. Individuals should have the option of purchasing Medicare coverage on state marketplaces. As an initial step, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should design an actuarially fair benefit package available on the new marketplaces for participants over the age of 60.

Raise or Eliminate Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income Asset Limits for People Living with Disabilities. The ACA does not impose asset limits for the Medicaid expansion population. Stringent asset limits remain, however, for individuals who qualify for Medicaid because of qualifying disabilities. States and the federal government should raise or eliminate these asset limits, which harm individuals with disabilities and their families.

Before the ACA’s passage, the United States had the most complicated health care financing system in the world. The ACA made that system even more complicated, by adding the new health insurance marketplaces, Medicaid expansion, and other innovations.

Employer-sponsored group coverage remains the foundation of our health financing system. Federal and state governments heavily subsidize this form of coverage through exclusions from federal income and payroll taxes and from state income tax of employer and often employee contributions for coverage. Americans have also traditionally obtained coverage through many other channels. The elderly and many people with disabilities, for example, qualify for Medicare, while certain categories of the poor have long qualified for Medicaid and then CHIP. Programs such as the Veterans’ Administration and Indian Health Services cover other specific populations. These various forms of health care and coverage are financed through multiple funding streams that are often poorly coordinated. Care and coverage are also regulated by different federal entities and by fifty state governments, whose priorities, political perspectives, administrative structures, and regulatory requirements are often quite different.

Although the ACA included reforms aimed at virtually all of the various pieces of our patchwork of coverage, it left most pre-existing programs largely intact. Most Americans continue to get health coverage as they always have, largely unaffected by the ACA. When the ACA did affect individuals’ existing health coverage, it primarily expanded coverage, for example by abolishing annual and lifetime limits for employer coverage, allowing coverage for young adults to age 26 under their parents’ plans, or closing the drug coverage “donut hole” for Medicare beneficiaries.

The most dramatic effect of the ACA has been to help people who were not previously covered. Before 2014, most working-age adults under age 65 who were not offered health insurance through employment were not eligible for any government assistance or tax subsidies to help them purchase health coverage. Many people were unable to afford health insurance unassisted.

The ACA took two approaches to extending coverage. First, it expanded Medicaid eligibility to cover individuals and families with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) who were not otherwise covered. Second, it offered tax credits on a sliding scale to individuals and families with incomes between 100 and 400 percent of the FPL—who were not otherwise offered coverage in government programs or affordable and adequate employer-based coverage—to help them purchase health insurance through state health insurance marketplaces. In 2015, individuals are thus eligible for financial help as long as their annual incomes are below $47,080. A family of four is eligible for some premium assistance at incomes less than about $97,000.

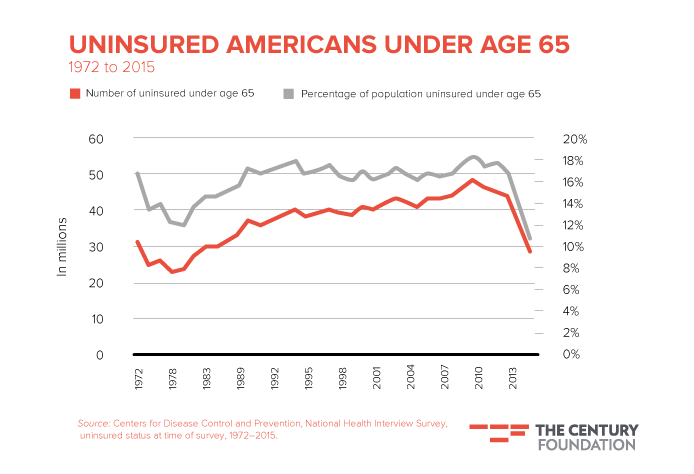

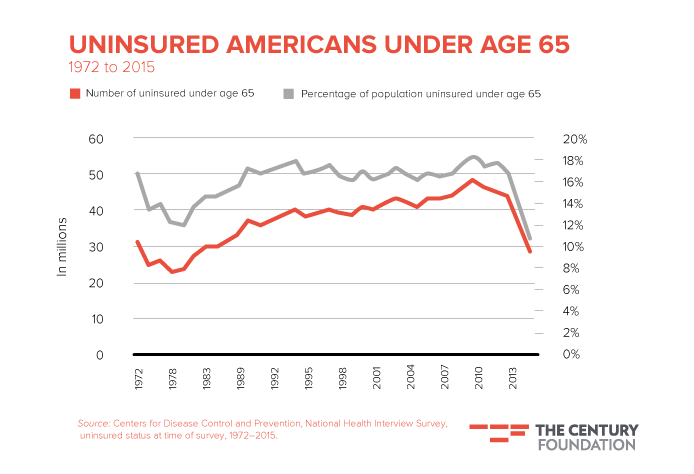

The Medicaid expansion has not reached all Americans. The Supreme Court’s 2012 decision in the National Association of Independent Business case seriously weakened the Medicaid expansion by allowing states to opt out. Currently more than three million adults in twenty states are uncovered because of that decision. 14 Even so, the ACA has cut the portion of currently uninsured American residents under age 65 from 18.2 percent in 2010 to 10.7 percent in 2015. 15

Furthermore, while the tax subsidy approach can claim many successes, it remains cumbersome and it has not been wholly effective. More than half of the 9 million moderate-income Americans currently enrolled through the ACA marketplaces were uninsured before they obtained such coverage. 16 Yet millions of Americans remain uninsured. Over 5 million of the uninsured remain uncovered because Congress deliberately excluded individuals not lawfully present in the United States from federal assistance. 17 Others remain uncovered, or may lose coverage, because the ACA premium tax credit assistance program is so complex, because they do not know that assistance is available, or because the cost of insurance, even with assistance, is still too high for them to afford. 18

We shall describe strategies for improving Medicaid coverage later in this report. The rest of this section will focus on gaps in and limitations of the tax subsidy approach to making coverage affordable for moderate-income Americans.

At the time the ACA was enacted, political realities dictated that assistance for moderate-income Americans must be provided through tax credits rather than through a new entitlement program.

Many of ACA’s greatest challenges arise from the basic reality that the subsidy structure is poorly suited to financing health coverage for low- and moderate-income Americans. 19 Political and cost constraints also limit the generosity of these tax subsidies, which compounds the challenge for millions of people who require financial assistance to purchase health coverage.

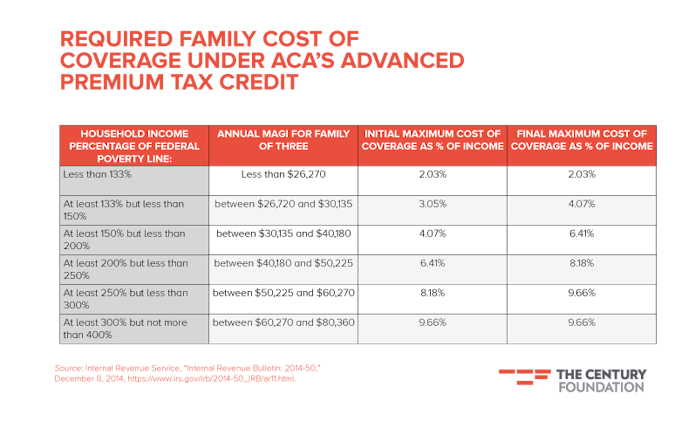

Those with incomes below 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible for at least some subsidies on the state marketplaces. Low- and moderate-income applicants for Advanced Premium Tax Credits (APTC) must predict their household income (actually, their modified adjusted gross income, or MAGI) for the entire coming year at the time of application (see Box 1). Yet the actual tax credits are based on retrospectively reported income as determined at tax-filing time.

Predicting household finances is especially challenging for individuals with fluctuating incomes. It is also difficult because household income includes not only the income of the applicant, but also the incomes of other household members. Even predicting household composition for an entire year may be challenging, as enrollees marry, divorce, have children, or die.

In relying on tax credits to expand coverage, the ACA follows a familiar strategy. Although America has maintained large health care entitlement programs for the elderly and poor, it has long relied—with bipartisan support—on the tax system to subsidize health coverage for the majority of Americans, who receive employer-sponsored coverage. 20

The IRS has demonstrated impressive administrative capacity to manage many aspects of this process, and has long operated programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which rank among the most successful and popular efforts to assist low-income Americans. Moreover, income-based tax credits, as opposed to fixed-dollar tax credits, are a reasonably effective way of ensuring that coverage will be roughly affordable regardless of a family’s income. The formulas used for calculating premium tax credits under the ACA also adjust payments to take account of premium variations in different insurance markets, household size, and the age of household members.

Yet the ACA’s program of advanceable tax credits is inescapably complex. Tax credits available under the ACA are often insufficiently generous to provide affordable coverage. Gaps in the current law also leave coverage unaffordable for many households. Were it politically possible, we would abandon the tax system as the mechanism of covering low-income Americans and extend Medicaid or Medicare or create a new program to do so. Given the daunting political obstacles to such approaches, we offer instead recommendations for improving the current system. We first address the biggest gap in the current program—the “family glitch”—and then the complexity of the tax credit approach.

The so-called “family glitch” may be the most glaring defect in the current ACA tax credit system. 21 Fixing the family glitch is essential to providing low-income working families access to affordable health coverage.

Under the ACA, workers are ineligible for marketplace tax credits if their employer offers them health insurance coverage that is deemed to be adequate and affordable. The family glitch arises because of the way in which affordability is actually defined. Current IRS regulations deem employer-sponsored coverage affordable if individual coverage (covering only the individual worker and not the worker’s family) costs less than 9.56 percent of household income. 22 (Throughout this report, affordability and eligibility levels will be provided in the inflation-adjusted percentages that apply for 2015. These percentages will be higher for 2016 and subsequent years).

This rule is fair for single workers, but not for many workers with families. Workers who need family coverage may be cut off from access to marketplace tax credits, even when the (much higher) cost of family coverage greatly exceeds 9.56 percent of income. 23 Many children in low-income families caught in the family glitch may be eligible for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). CHIP offers other advantages over marketplace plans, particularly for children experiencing significant health needs. However, half the states set the CHIP eligibility level at 255 percent of poverty or less, leaving many families excluded from marketplace coverage by the family glitch also unable to get CHIP coverage for their children. 24

Although the family glitch is often described as a legislative drafting error, it results from questionable statutory interpretation by the IRS (see Box 2). Whether this problem is addressed by Congress or administratively, and whether relief is extended to all individuals in affected families or just to dependents, it is important to provide working families the financial help they need to gain practical access to affordable health insurance.

RAND Corporation researchers recently examined two alternatives for fixing the family glitch. The first approach would allow all family members, including employed family members with access to affordable individual coverage, to be eligible for the APTC if employer family coverage were unaffordable; the second approach would give only dependents access to APTC subsidies. 25 (Alternatively, employees who lack access to affordable family coverage could be offered subsidized coverage to child-only policies. 26 ) Linda J. Blumberg and John Holahan of the Urban Institute performed similar analyses, and obtained consistent estimates. 27

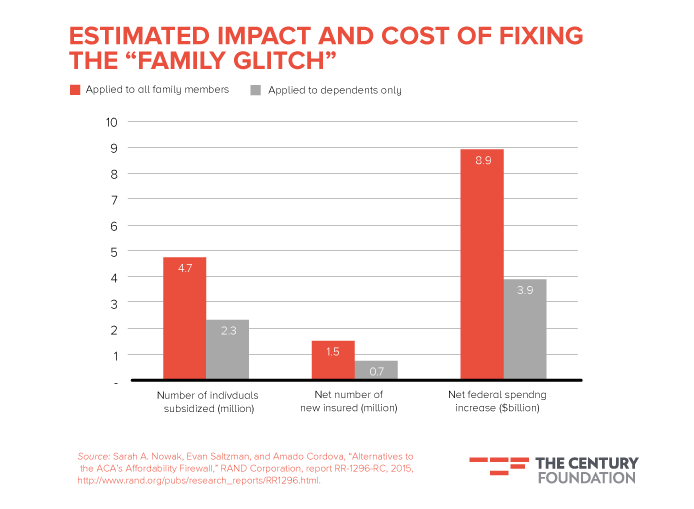

The RAND team estimates that granting eligibility to all family members would allow 4.7 million people to gain access to subsidized coverage, reducing the uninsured population by approximately 1.5 million people, with an accompanying net federal spending increase of $8.9 billion, slightly less than a 9 percent increase over the current baseline of $104 billion. The second approach would allow 2.3 million people to gain access to subsidized coverage, with an accompanying net federal spending increase of $3.9 billion, and a corresponding reduction of about 700,000 in the number of uninsured. (See Figure 3.)

Average spending for health care in 2017 for those affected by the change would decrease from a projected average of $6,564 under the current rules to $4,290 under the first option and $4,484 under the second. The proportion of affected working families spending more than 10 percent of their income on health care in 2017 would decrease from 87 percent under current rules to 47 percent under the first option or 58 percent under the second. Fixing the family glitch would come at some cost, but also would bring significant benefits for those who lack access to coverage because of it. It should be the place to start for expanding ACA coverage for families with incomes above the Medicaid eligibility level.

The complexity of the ACA’s tax credit program is daunting. To begin, many taxpayers cannot fulfill the ACA’s request of accurately projecting their household income a year in advance. Taxpayers earning less than 400 percent of FPL often experience variable work hours. Their incomes may depend upon the generosity of tip income, demand for a product or service, even, in many jobs, on the weather. A taxpayer or household member may gain or lose a job over the year, move from part-time to full-time status, or visa-versa. Moreover, tax credits are based on household size and composition. But household composition and size change, as babies are born, couples marry or divorce, people die, or older children become independent.

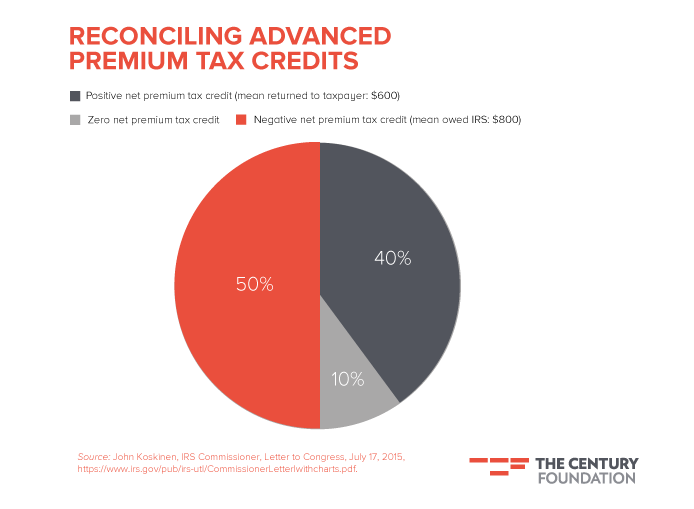

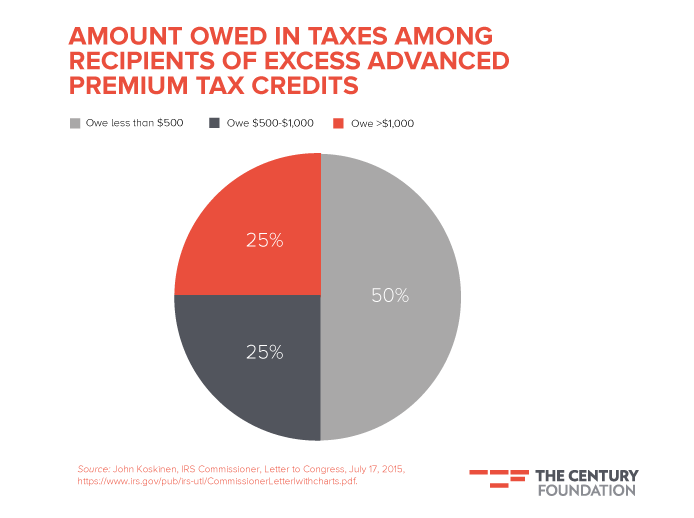

Tax year 2014 statistics on the functioning of the tax credit program reflected these uncertainties. In 2014, for only 10 percent of taxpayers eligible for the APTC did the credits paid out in advance equal the credits for which taxpayers were in fact determined to be eligible when they filed their taxes. 28 Fifty percent had to pay back excess APTC. Forty percent received additional tax credit amounts when they filed their taxes because they received too little APTC given their final income. Most (about 65 percent) of those who received excess APTC did not have to make a specific additional payment to the IRS because the excess amount was recovered from a tax refund to which they otherwise have been entitled. (See Figures 4 and 5.)

Yet another issue looms for APTC recipients who are not following through on their tax filing obligations under the ACA. As of June 2015, only 3.2 million of the 4.8 million taxpayers who were required to file a form 8962 to reconcile the APTC they received with the credits to which they were actually entitled had done so. 29 Taxpayers who fail to file these forms by the end of 2015 will not be entitled to reenroll for APTC for 2016.

One simple step to smooth the functioning of the APTC and avoid burdensome reconciliations would be to improve the accuracy of the credits by providing coverage applicants with a clearer and more comprehensive explanation of how their APTC was calculated.

Currently, applicants receive a statement when they become eligible that tells them the amount of their APTC and the amount of income on which APTC were based. Eligibility may be calculated based on the income reported by the applicant or on income drawn from prior tax records or other sources. A more transparent explanation could explain how the income was computed, including what income was considered in calculating the amount. The current notice informs the taxpayer that changes in income, available coverage alternatives, or household composition must be reported and that failure to do so may result in the taxpayer having to pay back overpayments, but the notice could include examples of how changes in household income or size might affect the amount the taxpayer would have to pay back.

Taxpayers could also be sent quarterly notices including the income projections on which their tax credits are calculated and advised to report any changes in income to avoid over- or under-payment of their APTC. Monthly premium statements from insurers could also remind enrollees of their obligation to keep enrollment information current. The issuance of the 1095-A form that enrollees are sent to assist with tax reconciliation could be moved up to mid-January to ensure that taxpayers received early notice of their need to file taxes and the amount of APTC on which their taxes would be calculated.

The reconciliation process could also be adjusted to ease the burden of reconciliation. Under current regulations, applicants’ income estimates need no verification if estimated income is no more than 10 percent below the amount found in other data sources, such as tax records. 30 In fact, the federally facilitated marketplace will accept a 20 percent variance based on a taxpayer’s income attestation when validating taxpayer income claims. 31 Of the 1.6 million taxpayers who had to repay excess APTC for 2014, half owed less than $500. Of the 1.3 million who were underpaid, 65 percent received less than $500. 32

Allowing some variance from projected to actual income at the time of reconciliation could reduce administrative complexity and taxpayer burden. Taxpayers could be excused from having to pay back tax credits if their final household income were within a certain percentage (perhaps 10 percent) of their projected income, as long as the taxpayer did not intentionally underreport income. Taxpayers who were determined to have received less in APTC than they were entitled by the same percentage of variation would not receive an additional payment unless they had intentionally foregone advance payment of the full tax credit. The total amount that an individual would have to repay would still be subject to caps, although these should be reduced from the current amounts to amounts closer to those found in the original ACA ($250 for individuals, $400 for families). 33

Taxpayers should also have the option of the IRS reconciling their APTC and actual premium tax credits rather than having to do it themselves. The IRS has access to most of the information available to taxpayers for determining the credit—most importantly the total amount of APTC received and number of covered family members reported on the 1095-A, and the final amount of the taxpayer’s income, reported on form 1040. 34 Taxpayers should have the option of reconciling the amount of APTC they received and the amount to which they were entitled using the form 8962—the tax reconciliation form–and would have to do so if special circumstances apply, such as a mid-year marriage. If they fail to do so, however, the IRS could simply perform the reconciliation calculation for them, assuming the information on form 1095-A to be correct. Taxpayers could be notified on the form 1095-A that the IRS will perform the reconciliation calculation for them if they fail to file a form 8962. No one should lose access to premium tax credits simply because they fail to file this form.

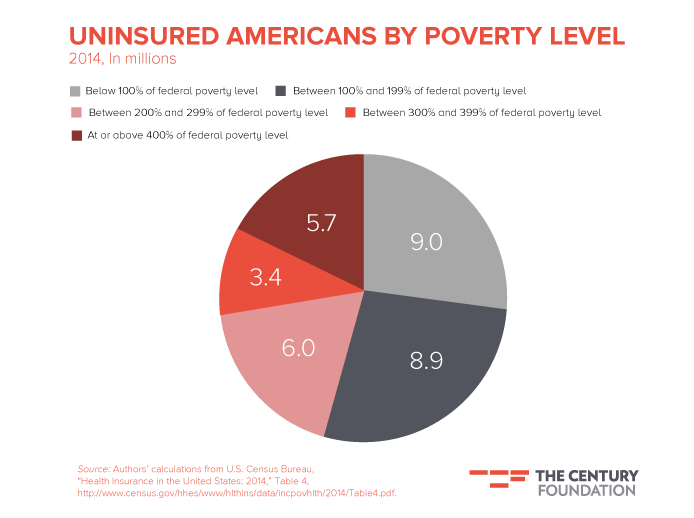

Although Medicaid, tax credits, and cost-sharing reduction payments help make insurance affordable, health insurance is still so costly for many moderate- and middle-income Americans that they refuse coverage. 35 An estimated 9 million Americans with incomes exceeding 300 percent of the poverty line are uninsured (see Figure 6).

Current tax credits require individuals and families with incomes below 200 percent of FPL to pay too much before tax credits take over. One consequence is that many low-income workers are declining subsidized employer-based and marketplace-based coverage. One employer noted to the New York Times’ Robert Pear that persuading hourly workers to buy insurance is “like pulling teeth.” Most workers whose weekly take-home pay is about $300 will not spend $30 of that on insurance, particularly on policies with significant deductibles and copayments. 36

Reducing (or eliminating) premiums for Medicaid-ineligible families below 150 percent of the FPL would greatly improve take-up among those in greatest need. Affordability is also a problem among those with higher incomes. More than 15 million uninsured Americans have incomes in excess of 200 percent of FPL, while 5.7 million uninsured have incomes above 400 percent of the poverty level. 37

Households with incomes above 400 percent of FPL are not entitled to financial assistance, and few have sought coverage through the marketplaces. 38 The current structure imposes an additional implicit marginal tax rate on enrolled individuals whose incomes increase, with a particularly high “notch” at 400 percent of FPL, where APTC eligibility ends. The full schedule of ACA subsidies could potentially (particularly in combination with income limits of other federal and state anti-poverty programs) create adverse work incentives. They also impose significant burdens on middle-income Americans who lack access to employer-sponsored coverage.

Urban Institute researchers Linda Blumberg and John Holahan have proposed raising the APTC to make health insurance more affordable. 39 Households with incomes at 200 percent of the FPL would see the amount they would have to pay for premiums out of their own pocket reduced from 6.34 percent of income to 4 percent, while those at 300 percent of poverty would see a reduction from 9.56 percent to 7 percent. Blumberg and Holahan also propose allowing individuals with incomes above 400 percent of FPL to gain access to tax credits, as long as the premiums they would have to pay for the second-lowest-cost gold plan cost more than 8.5 percent of household income. Thus assistance would not be linked only to the amount of income but also to the cost of coverage. Adoption of this proposal would improve access to affordable health insurance for moderate- to middle-income households. Yet its cost would not be open ended, as the number of households that would be eligible for coverage would rapidly diminish as income increased.

Another approach would be to combine fixed-dollar, age-adjusted tax credits with ACA’s income-based tax credits. Middle-income taxpayers without access to employer coverage would at least be entitled to a fixed-dollar tax credits even if their incomes were too high to qualify for income-based credits.

From both a substantive and a political perspective, such proposals merit consideration. Fixed-dollar tax credits have long been proposed as an alternative to the current employer-sponsored insurance tax exclusion. These proposals have come primarily from conservative or libertarian advocacy groups, but have also been put forward by many economists across the political spectrum.

Under one proposed alternative, taxpayers who do not have employer-sponsored coverage could choose between income-based tax credits, which could continue to phase out at 400 percent of FPL based on the cost of coverage, as described above, and fixed-dollar tax credits, which could be more generous than income-based tax credits at the 400 percent of poverty level. The amount of the credits should be set high enough to have a significant effect on affordability, but would still leave most of the responsibility for the cost of insurance with enrollees at higher income levels. Credits should be age-adjusted to ensure that they reflect age-related premium differences. These could also phase out at higher incomes, for example providing no assistance above the ninetieth percentile for household income ($150,000 in 2013). 40

Such credits should be limited to individuals who are not covered through their work, since employer-sponsored coverage is already tax subsidized. However, individuals offered coverage through their work should be able to decline that coverage and purchase coverage through the marketplace and claim tax credits if this alternative is more affordable. This program structure may lead some employers to stop offering coverage, as firms and workers compare the value of the fixed credit to the value of the tax exclusion. As long as marketplaces offer good coverage, we regard this as an acceptable policy tradeoff.

Fixed-dollar tax credits for higher-income individuals would not require reconciliation based on actual income or to repayment to the Treasury, as long as total household income remained below the maximum eligibility level. Fixed dollar tax credits would thus be more predictable and simpler than income-based tax credits. It may not even be necessary to pay them in advance, as taxpayers could reduce withholding or estimated tax payments in anticipation of the credits and use the savings to help pay for health insurance.

A fixed-dollar tax credit such as that proposed here would come at some cost. Since it would only be available to individuals who do not enroll in employer coverage and who did not qualify for income-based credits, it would be much less costly than a universal tax credit. One attractive pathway to finance this system would be to cap the employer-sponsored coverage tax exclusion, a proposal that has wide support in the policy research community. Further research is needed to determine the amount of tax credits, their total cost, and how they would be financed.

The ACA has reduced the financial burdens associated with injury and illness, and has made health care more affordable for millions of Americans. 41 Yet this coverage often comes with high deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments, 42 a pattern that reflects continuing trends within employment-based coverage as well.

Although ACA provides valuable limits on total out-of-pocket spending, it has not restrained the long-term trend toward higher deductibles and copayments in employer-sponsored coverage. Higher cost-sharing indisputably reduces the volume of care received by consumers, and thus overall expenditures. Yet there is considerable and growing evidence that such cost-sharing does so indiscriminately, reducing consumption of high-value as well as low-value care. 43 This is a particular problem for low-income individuals who cannot afford high cost-sharing levels, especially low-income people who experience significant health needs.

Covered individuals increasingly seek care from narrow provider networks and find medications listed on limited or tiered formularies. 44 Indeed some plans have implemented narrower networks to reduce annual deductibles in marketplace plans. 45

While narrower networks can provide high-quality, cost-effective care, too-narrow networks or formularies can pose significant barriers to consumers getting the care they need. In-network providers are not always easily identified, and out-of-network providers are not easily avoided. People served by out-of-network providers may therefore face large and unexpected bills. 46

In sum, the ACA has expanded coverage, but too many Americans lack access to affordable and transparently priced health care. This section addresses problems raised by excessive cost-sharing and networks and formularies that are too restrictive.

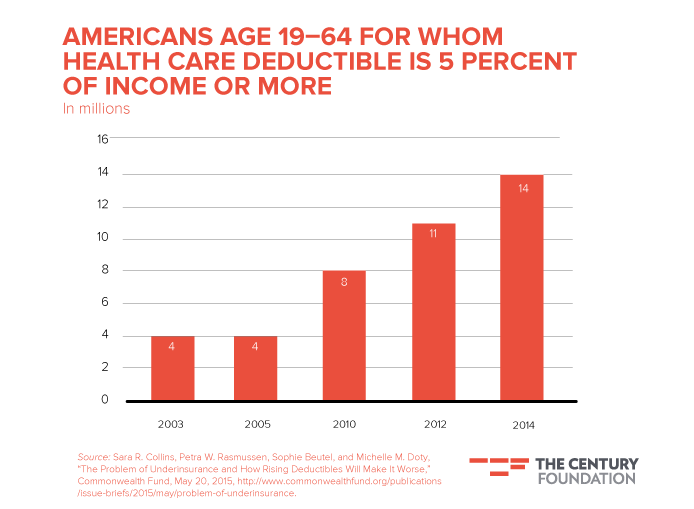

Although the ACA implements stop-loss provisions that reduce the risk of catastrophic financial loss, out-of-pocket medical costs continue to be a major concern for many Americans. Eleven percent of insured adults now have deductibles of at least $3,000, compared to 1 percent in 2003, while 38 percent have deductibles of $1,000 or more, compared to 8 percent in 2003. 47 Adjusting for inflation, out–of-pocket expenses have steadily grown. 48 (See Figure 7.)

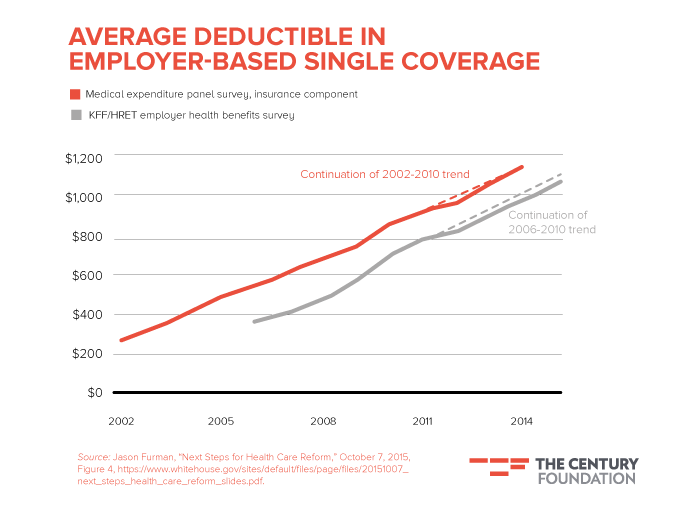

The ACA is sometimes wrongly blamed for increasing consumer out-of-pocket spending, so far the new law appears to have neither aggravated nor slowed the long-term trend toward higher deductibles and copayments in private coverage (see Figure 8).

High cost-sharing is having a real impact on American families. A recent Commonwealth Fund study finds that half of underinsured adults report being contacted by collection agencies or having to change their way of life because of medical bills. 49 Almost half reported having used all their savings or receiving a lower credit rating, while 7 percent declared bankruptcy. 50

Being underinsured also has medical consequences—a quarter of those responding to the Commonwealth survey reported not going to the doctor for a medical problem, not filling a prescription, or skipping medical tests or treatments recommended by a physician for financial reasons. For those in deep poverty, any cost-sharing obligation—even a $2 copayment—can result in reduced access to medical care. 51 Many newly insured Americans are particularly unfamiliar with the structure of deductibles and copayments, and may thus be unprepared for cost-sharing obligations. 52 (See Figure 9.)

The ACA has a confusing array of rules governing the adequacy of coverage that can, in some circumstances, leave care essentially unaffordable. ACA requires individuals who can afford coverage and do not otherwise qualify for an exemption to have “minimum essential coverage.” 53 Minimum essential coverage could be coverage through an employer, a government program, or individual coverage. Large employers (with more than fifty full-time equivalent employees) are required to provide minimum essential coverage to their full-time employees or to pay a penalty for each full-time employee if any employee receives premium tax credits for non-group coverage through the marketplace.

As applied to employer coverage, the minimum essential coverage definition requires vanishingly little. 54 Minimum essential coverage provided by employers must cover preventive services without cost-sharing, cannot impose annual or lifetime dollar limits, and cannot consist merely of “excepted benefit” plans, such as cancer or dental policies. Yet a “mini-med” policy that covered, say, only three physician visits and one day of hospitalization, in addition to preventive benefits, could conceivably pass muster.

Even if their employers offer minimum essential coverage, employees who are otherwise eligible for coverage can decline it and purchase coverage through the marketplace and receive APTC, if their employee does not offer them “minimum value coverage” that they can purchase for 9.56 percent or less of their modified adjusted gross income (MAGI).

Minimum value employer coverage is somewhat more comprehensive than minimum essential coverage. Minimum value employer plans must have an actuarial value of at least 60 percent (that is, they must cover at least 60 percent of the costs of a standard self-insured-plan population) and they must cover substantial hospitalization and physician services—but minimum value plans can still impose substantial cost-sharing on employees. 55

Individual and small group insurance must meet higher standards (although it often in fact imposes higher cost-sharing than most large-employer plans). It must cover ten essential health benefits and provide coverage after cost-sharing set at one of four actuarial value levels—bronze (60 percent), silver (70 percent), gold (80 percent), and platinum (90 percent). 56 “Catastrophic plans” (which have deductibles equal to the statutory out-of-pocket limit and only cover preventive services and three primary care visits annually but have actuarial values of less than 60 percent) are also available to young adults and individuals for whom other non-group coverage is unaffordable. Premium tax credits are keyed to the premium of the second lowest-cost silver plan in a market. Most marketplace enrollees who depend on premium tax credits choose to purchase bronze or silver plans. 57

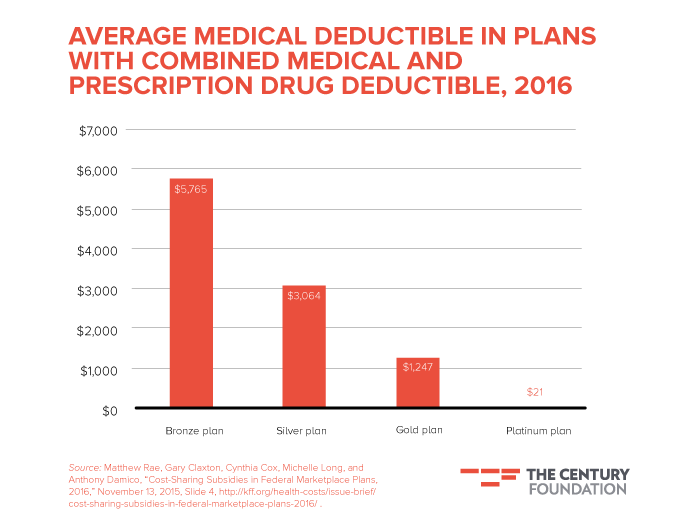

Bronze, silver, and catastrophic plans bring high cost-sharing. For 2015, bronze plans with combined medical and prescription drug deductibles averaged $5,200 for individuals and $10,500 for families, 58 while silver plan deductibles average $3,000 for individuals and $6,000 for families. 59 High cost-sharing allows lower monthly premiums. But high cost-sharing can impose significant burdens, particularly those with modest incomes or costly health challenges. Lower-income families may face a choice between affordable coverage and affordable care.

Out-of-pocket costs for all ACA-compliant group health and individual insurance plans are also capped for 2015 at $6,600 for an individual and $13,200 for a family. 60 These caps provide important protections for many families experiencing serious injury or illness, yet they still exceed the available cash assets of many Americans. Indeed, a 2014 Federal Reserve survey found that 47 percent of Americans could not come with more than $400 without selling something, borrowing from a friend or relative, or taking out credit card debt or a payday loan. 61

Other serious cost-sharing burdens remain. 62 The cap only applies to in-network services. Insurers and group health plans can cover services from out-of-network providers but are not required to do so (except for emergency services) and often impose higher caps on out-of-network out-of-pocket expenditures. Out-of-pocket caps also do not apply to services that do not qualify as essential health benefits.

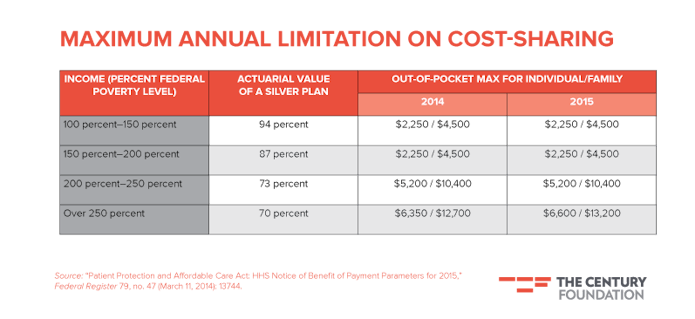

Although a standard silver plan is one that covers 70 percent of the actuarial value of covered services, the ACA also provides cost-sharing subsidies that boost the total value of a silver plan for marketplace enrollees with incomes below 250 percent of the FPL.

Such assistance is greatest for those with incomes below 150 percent of the FPL (about $36,000 for a family of four), whose coverage has an actuarial value of 94 percent. Assistance is then reduced, and constraints on out-of-pocket payments gradually reduced up to 250 percent of the FPL (about $60,000 for that same family). 63

Households with incomes above this threshold, particularly those who receive out-of-network care, are often responsible for far higher out-of-pocket payments, even if their household incomes are below 400 percent of FPL and they therefore remain eligible for financial assistance with their monthly premiums. The ACA requires the federal government to reimburse health plans for the amounts they provide modest-income consumers in reducing cost-sharing. Litigation is now pending challenging the legality of this reimbursement in the absence of explicit congressional appropriation. 64 Even as it is now applied, the ACA does not go far enough.

The ACA should be amended to make health care more affordable. Cost-sharing should be reduced to reduce patients’ financial burdens, and to avoid deterring patients from seeking valuable care. Urban Institute researchers Linda Blumberg and John Holahan propose that the premium tax credits be set to cover the cost of 80 percent actuarial value gold plans rather than the 70 percent silver plans. 65 These researchers also propose that actuarial values be increased to 90 percent for individuals with incomes between 150 and 200 percent of FPL and to 85 percent for individuals with incomes between 200 and 300 percent of FPL.

Running these provisions through Urban’s microsimulation models, these researchers estimate that such changes would increase federal expenditures for ACA insurance affordability programs by $221 billion over ten years. 66 We support this proposal.

Health care could also be made more affordable by reducing out-of-pocket limits. As noted above, the ACA imposes an out-of-pocket limit on all forms of health coverage. 67 Under the ACA, this limit was supposed to be reduced by two-thirds for households with marketplace coverage with incomes below 200 percent of FPL, half for households with incomes between 200 and 300 percent of FPL, and one-third for households with incomes between 300 and 400 percent of FPL.

The ACA provided, however, that these reductions in out-of-pocket limits should not increase the actuarial value of plans above the limits set for cost-sharing reduction payments. 68 As a practical matter, this has meant that out-of-pocket limits have not been reduced for individuals with incomes above 250 percent of FPL because to do so would require insurers to cover a larger share of claim costs and thus increase the actuarial value of coverage above the 70 percent silver plan actuarial value limit. Thus, while out-of-pocket limits are reduced by two-thirds for enrollees with incomes below 200 percent of FPL, out-of-pocket limits are reduced by less than a third for individuals with incomes between 200 and 250 percent of FPL, and not at all for those with higher incomes.

Significant cost-sharing relief could be afforded individuals with moderate incomes by effectuating the out-of-pocket limits imposed by the ACA without regard to actuarial value. If the actuarial value of ACA benchmark plans were increased from 70 to 80 percent, as Blumberg and Holahan suggest, the out-of-pocket limit could be decreased across the board to the levels found in the original ACA, since insures could pay a larger share of total covered costs.

Finally, the ACA employer responsibility regulations should be amended to improve coverage. Minimum value coverage should include substantial coverage for pharmacy and diagnostic tests as well as hospitalization and physician services. Minimum essential coverage should require coverage of hospital, physician services, pharmacy, and diagnostic tests as well. Employers who fail to provide these services should be subject to the employer mandate penalties. Employees who are not offered minimum value coverage as redefined should have access to marketplace coverage with premium tax credit support. As noted below, principles of value-based insurance design may prove helpful in defining the scope of coverage in these areas.

Cost-sharing reduction payments are only available to individuals who purchase individual qualified health plans through the marketplaces and who are otherwise eligible for APTC assistance. This leaves millions of individuals with coverage through their employment or through the individual market with incomes above 400 percent of FPL exposed to levels of cost-sharing that may still make health care a significant economic burden.

One way of increasing affordability for middle-income populations is through account-based programs such as health savings accounts (HSAs), health reimbursement accounts, flexible spending plans, and Archer medical savings accounts. These accounts permit tax subsidies for amounts set aside to cover medical costs, including cost-sharing imposed by health plans.

HSAs are sometimes touted as an all-purpose solution to health policy problems. In fact, HSAs provide one of the most heavily subsidized investment vehicles available and are used disproportionately by affluent taxpayers, who use them to maximize retirement savings rather than simply paying for health care, as money can be withdrawn from HSAs after age 65 for non-health care expenses without a penalty. 69 Simply increasing the generosity of federal subsidies for HSAs for people in high-tax brackets will not make health care more affordable for those who need help.

HSAs can, however, be of value to marketplace enrollees. For example, HSA contributions can provide “above the line” deductions to reduce modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). Since the MAGI is the income amount used to calculate APTC eligibility, a marketplace enrollee can by investing in an HSA both increase APTC and increase funds available to cover cost-sharing obligations. While it would be preferable to increase APTC and cost-sharing reduction eligibility levels and generosity, if this is not politically possible, HSA investments can provide some relief for individuals with moderate incomes or individuals who underestimate their income and are faced with high APTC repayments at tax filing time.

Some legislative changes could make HSAs even more helpful for those who actually use them to cover health care costs. First, the out-of-pocket limits under the ACA could be amended to align them with out-of-pocket maximums for HSA-linked high-deductible health plans. Although the limits were initially aligned, they increase under different inflation adjustment rules, making it possible that ACA compliant plans would not be HSA eligible. For 2016, for example, the maximum out-of-pocket expenditure limit for health savings account compliant high-deductible health plans is $6,550, 70 while the maximum ACA out-of-pocket limit is $6,850. These rules could be easily aligned.

Modest direct federal contributions to HSAs for moderate-income Americans could also be considered. These could be made available in fixed amounts ($500 per year, for example) to middle-income individuals who are not eligible for cost-sharing reduction payments but who have incomes below certain levels, perhaps 500 percent of FPL. These could be paid as a refundable tax credit at the time of tax filing based on actual taxable income, avoiding the need for reconciliation. 71 They could be made to individuals with employment-related coverage as well as individual market coverage.

As with retirement accounts, modest subsidies could be implemented with a well-designed choice architecture that could overcome behavioral inertia to encourage greater savings. 72 For example, the federal government could implement a matching-contribution framework. Government or private plans could also assist consumers with the logistical practicalities of establishing such accounts.

Consideration should also be given to allowing small employers to fund health reimbursement accounts (HRAs) that could be drawn upon by employees to purchase health insurance in the individual market. This is currently illegal under administration interpretations of the ACA and preexisting tax law. 73 Protections would be required to ensure that employers treated all employees the same and did not use this possibility to dump high-cost employees into the marketplaces. Provision would also have to be made to ensure that the offer of an HRA did not disqualify employees from receiving marketplace premium subsidies unless the HRA contribution made coverage genuinely affordable. Finally, “double-dipping” should not be permitted—employees should have to choose between employer HRA-financed coverage and APTC, and not receive both. But with these protections, found in current legislative proposals (HR2911), a program that allowed small employer contributions for coverage through HRAs could encourage some employers who would not otherwise offer traditional small group coverage to make coverage more affordable for their employees. 74

Even if the ACA is not amended to increase cost-sharing support, health insurers could make health care more affordable. Some marketplace plans currently offer some services—coverage of generic drugs for example—that are not subject to the deductible. 75 Others permit limited access to some services—three primary care visits for example—before the deductible applies. In fact, in 2015, 80 percent of marketplace silver plan enrollees selected a plan with a primary care visit covered before the deductible while 82 percent selected a plan with generic drugs covered below the deductible. 76 These plan designs could be encouraged (or required) by the marketplaces—including the federal marketplace—which are required under the ACA to ensure that qualified health plans are “in the interests of” plan enrollees.

Such plan designs carry some danger of risk selection. If these plans impose lower cost-sharing on individuals with minimum medical demands, they must make up for it by imposing higher cost-sharing elsewhere, presumably on higher-cost individuals. On the other hand, if offering some covered services to individuals with low medical needs attracts those individuals into the marketplace, this might have the effect of lowering the cost of coverage for all marketplace participants.

As noted above, accumulating evidence confirms that greater patient cost-sharing leads to reduced utilization. But there is little evidence that consumers respond to cost-sharing by effectively comparing prices for costly services, or by focusing on the highest-value care. 77

Zarek C. Brot-Goldberg and colleagues, in a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, examined the experiences of workers who were shifted from a no-deductible plan to one with a $3,750 deducible linked with a correspondingly generous $3,750 health savings account. 78 Consumers were also provided innovative online shopping tools that were intended to assist them in comparing prices for doctors’ visits and various accompanying services and tests. Annual medical spending quickly dropped, with total firm-wide medical spending declining by more than 10 percent. 79 Yet the decline was undiscriminating. Brot-Goldberg and colleagues found little evidence that workers effectively distinguished wasteful from valuable care. Given a financially generous high-deductible health plan with an accompanying HSA, even this group of relatively high-income, highly educated workers markedly reduced its receipt of clinical preventive services and other valuable care. 80

There was also little evidence that this relatively advantaged consumer group used available tools to identify cheaper services and providers, or even that consumers strategically responded to the actual economic incentives created by their insurance plan. Researchers found especially concerning utilization declines among people with health problems, who may have foregone important forms of care. Almost half of the spending reduction also occurred among predictably sick individuals likely to exceed their annual deductibles, for whom the true marginal cost of specific services was often quite low. This overall pattern of findings casts doubt on the power of calibrated consumer incentives to safely and effectively improve the cost-effectiveness of medical care.

Value-based insurance design (VBID) attempts to balance the competing goals of greater economy and cost-effectiveness with greater financial protection and improved health. Consumers require the most generous coverage and most minimal cost-sharing for high-value services likely to improve health, with less generous cost-sharing for lower-value services such as name-brand drugs for which cheaper generic substitutes are readily available.

The ACA incorporates one form of VBID by requiring insurers to cover clinical preventive services without patient deductible or copayment when these are granted an “A” or “B” rating by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force based on rigorous clinical trials. Equivalent bodies could develop an evidence-based list of secondary prevention and chronic disease management services that would similarly be covered without patient out-of-pocket cost or with minimal cost. 81

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation recently announced an initiative to deploy VBID principles to align cost-sharing more carefully with high-value services in Medicare Advantage. Beginning in January 2017, these programs will test the utility of structuring patient cost-sharing and other health plan design elements to promote high-value clinical services in seven states. This effort provides a promising platform to design more innovative marketplace plans, which the federal and state marketplaces should encourage. 82

Further steps should be taken to improve the adequacy of provider networks and formularies. Consumers also need to be protected from surprise balance billing when they unintentionally use the services of out-of-network providers. This could be done by amendments to the ACA, but could be accomplished also by the administrative actions under existing authority and by state legislatures and insurance regulators.

Narrow provider networks are a familiar feature in American health care. These have become only more common and narrower in recent years, due largely to the concurrent effects of rising costs and competitive pressure on insurers to reduce premiums. As a result, insurer provider networks cover an ever smaller roster of providers to reduce costs from the insurer’s perspective, thus permitting lower premiums.

With proper transparency, narrow networks can benefit consumers. Narrow networks provide insurers (and thus their customers) greater leverage to constrain prices and to maintain quality. 83 Excessive regulation of networks is problematic if regulations unduly tie the hands of insurers and consumers in provider negotiations. 84

But narrow networks can leave consumers without necessary access to providers. 85 If networks include too few providers, or if none of these providers are accepting patients or can communicate in an enrollee’s language, enrollees may be denied care that they need and have contracted to receive. If providers are too far away, if delay times to obtain appointments (or the times in the waiting room after arriving for an appointment) are too great, the enrollee can effectively be denied coverage.

If an enrollee has special needs—pediatric oncology or HIV therapy, for example—and a network lacks providers that can provide specialized care, the enrollee may lack practical access to the most essential benefits of their insurance coverage. Moreover, some insurers might intentionally restrict networks to deter high-cost patients from enrolling. A particular concern is that insurers may restrict drug formularies to discourage individuals who need access to high-cost specialty drugs from enrolling in their plans. 86

Recent analysis of plans available in six cities found that most marketplace plans include at least one marquis hospital or academic medical center. 87 Such participation is quite salient to both consumers and regulators, and is perhaps essential for a credible commercial product. But physician network adequacy is more complex and less readily observed by consumers. Proper regulation is therefore essential to ensure access and to avoid risk selection across plans.

The ACA marketplaces oversee network adequacy for qualified health plans (QHPs). QHP networks must, under the federal rules, include a sufficient number and variety of types of providers, including mental health and substance abuse providers, to ensure that all services are available without unreasonable delay. 88 Current marketplace regulatory oversight focuses on access to hospital systems, mental health, oncology, and primary care providers. QHP plans must also include essential community providers that serve low-income and medically underserved individuals. QHP insurers must make provider directories available online and in hard copy and must update their online directories monthly. If necessary in-network care is unavailable, plans should be required to pay for out-of-network care with in-network cost-sharing.

QHPs must also cover at least one drug from each U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention category and class and the same number of drugs in each category and class as the state’s essential health benefits benchmark plan. QHPs must provide an exceptions process for enrollees who need drug not on the formulary and cannot discriminate through the use of their formulary, for example, by excluding HIV drugs.

The Department of Health and Human Services also regulates network and formulary adequacy for Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans. Regulation of Medicare Advantage plans has become quite sophisticated, with a focus on geographic accessibility of providers, 89 while regulation of Medicaid plans will be tightened up under recently proposed regulations. 90 Employer plans need only describe their network provisions and provide a list of their network providers. 91

Regulation of network adequacy is, therefore, primarily the responsibility of state insurance regulators. State regulation, however, varies widely, while advocates and the news media are more focused on Washington, D.C. than on the fifty state capitals where the most critical decisions will be made. Therefore, progress on this front will require improving state regulatory efforts directed at network adequacy.

Although the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) has had a managed care plan network adequacy model act since 1996, fewer than one-quarter of states had adopted the model, as of a recent survey. 92 While most responding states reviewed plans of health maintenance organizations for compliance with network adequacy standards, far fewer performed similar reviews of preferred provider organizations, except when complaints were received. Only about half the states imposed quantitative standards in place for evaluating time and distance to providers 93 . Only about one-fifth limited how long enrollees must wait for an appointment with providers or require minimum ratios of enrollees to providers. 94 Most states did not require network directories to be updated more often than annually. Many states did not affirmatively monitor ongoing network adequacy for non-HMO plans unless they received a complaint.

A program for regulation of network adequacy has been proposed by the consumer representatives to the NAIC. 95 Much of this program is included in a redraft of the model law recently adopted by the NAIC. Under the program proposed by the consumer representatives, states should have to adopt network adequacy regulations governing all insured plans that use networks—that is, virtually all insurance plans. States should ensure consumers’ accessibility to providers within reasonable distances and without unreasonable waiting times for appointments. Access should be guaranteed to the full range of providers needed by plan enrollees, with an emphasis on primary care, mental health and substance abuse care, and care for children. Failure to include providers necessary to address certain conditions should be treated as a discriminatory benefit design issue. Regulators should also ensure that formularies are adequate and non-discriminatory, and that an exceptions process is readily available.

Regulations should also require insurers to enroll at least some providers that offer extended hours and weekend appointments. State regulators should pay special attention to access to essential community providers. Regulators should also ensure that health plans not only have network contracts with hospitals, but also with physicians within those hospitals, particularly with hospital-based physicians such as anesthesiologists, radiologist, pathologists, emergency room doctors, and hospitalists.

Insurers should be required to file access plans that describe in detail their networks, how those networks adequately address the needs of their enrollees, and how pertinent and timely information about their networks is clearly communicated to consumers. The access plans should in particular address the criteria an insurer uses to select providers, including measures that address quality of care, and protocols for maintaining and updating network directories. These access plans, and any changes to them, should be reviewed and approved by regulators before they go into effect.

Regulators should regularly review compliance with network adequacy regulations, using such tools as secret shoppers and review of provider contracts to ensure adequacy. Regulators should not passively rely on complaints to ensure insurer compliance. Regulators should also not simply rely on accreditation status to ensure network adequacy. Accreditation can provide an additional check on adequacy, but cannot substitute for public regulation.

Some enrollees will inevitably be unable to receive needed care in network plans. All network plans should thus be required to provide an exceptions process for enrollees who cannot find within-network providers, either because of their specialized needs or because of network capacity. Requests for exceptions in urgent cases should be handled within twenty-four hours. Regulators should collect routinely data to monitor the frequency of use of out-of-network providers, the cost of out-of-network services, and the use of the exceptions process.

Consumers should also be protected when their providers leave their plan’s network. Providers should be required to ordinarily give ninety days’ notice to health plans before terminating their contractual participation. Network providers (or the plans) should give the same notice to patients under treatment before the provider is allowed to disenroll from a plan’s network. If a provider and a plan terminate their contract or a provider is moved from one cost-sharing tier to a different tier, an enrollee who is pregnant, terminally ill, or under a course of treatment for a serious condition should be able to continue treatment at the same cost-sharing level for ninety days, or until a baby is delivered or the condition resolved. If an enrollee’s primary care physician or provider with whom they are in active treatment leaves a plan in the middle of a plan or policy year, the enrollee should also be given a special enrollment period to move to a plan in which their provider is enrolled.The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has recently proposed regulations that would require federally facilitated marketplace qualified health plans to provide similar continuity of care protections.

Consumers should be protected from balance billing unless they have freely assumed the risk by knowingly seeking care from a non-network provider fully aware that they will receive a balance bill. 96 Consumers who receive emergency care from an out-of-network provider should not need to pay more just because they could not get to an in-network provider. Federal law now requires network plans to pay minimum provider rates and to not charge consumers higher coinsurance or copayments for out-of-network emergency care. It does not, however, ban balance billing in emergency situations. A few states have laws requiring insurers to hold consumers harmless for emergency out-of-network care, but many states do not. 97 All states, and the federal government for QHP plans, should adopt laws holding insured individuals harmless from balance billing when they must receive out-of-network emergency care.

Protections are also needed for consumers who have exercised reasonable caution to make sure that they are receiving treatment from in-network providers but nonetheless receive out-of-network services, for example from anesthesiologists, pathologists, or surgical consultants. CMS has recently proposed a rule under which a marketplace health plan could provide notice to an enrollee at least ten days in advance of the receipt of services from an in-network facility that there was a possibility that the enrollee might receive out-of-network services while at the facility. If a plan failed to provide this notice, any cost-sharing imposed by out-of-network providers would have to be charged against the plan’s out-of-pocket limit so that the insurer would absorb costs above that limit. This is a step in the right direction, but does not go far enough.

When consumers schedule a procedure with an in-network provider in a nonemergency situation, they should be informed as to whether professionals that might be involved in the procedure are out-of-network and, if so, be offered the option of choosing in-network providers. If consumers end up being treated by out-of-network providers despite reasonable efforts to receive only in-network care, an arbitration process should be provided to resolve the issue between the provider and insurer without involving the consumer. “Final-offer” arbitration, in which the parties, in this case the provider and insurer, each submit bid amounts and the arbitrator chooses one or the other, is one simple process for reaching a reasonable solution to balance billing disputes. 98 The recently finalized NAIC model act provides a similar approach, requiring mediation or negotiation of large balance bills between the insurer and provider.

One goal of the ACA is to provide consumers with a range of health plan choices. Another is to encourage competition among insurers to constrain premium growth and improve quality and value. To accomplish both of these ends, the ACA created exchanges—now called marketplaces—where consumers can shop for individual and small group coverage and insurers can compete for their business.

The ACA constrains marketplace choices and competitions in several ways. Insurers are restricted from competing in the way they have traditionally—by avoiding high-risk enrollees or charging them higher premiums. Insurers also cannot compete in the individual and small group market by offering skinny benefit packages. All insurers in these markets must cover a reasonably comprehensive package of essential health benefits. Qualified health plans sold through the marketplaces must also meet other requirements, including inclusion of essential community providers that cover low-income and high-need enrollees, and accreditation by recognize accrediting entities.

Within these constraints, insurers are free to compete for consumer business, and consumers are free to choose the plan that they think best suits their own needs and resources. Although the extent of competition, and the ways in which insurers have competed, have varied from state to state, and from one region to another within a given state, competition has been robust throughout much of the country. Consumers have, on average, five insurers and fifty health plans to choose from per county in the 2016 open enrollment period. 99

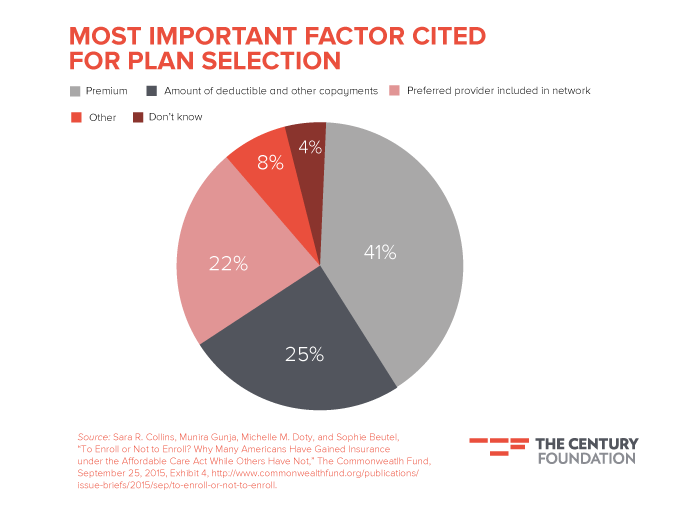

Insurer competition has focused intensively on premiums. In a recent Commonwealth Fund survey, 41 percent of participants reported that low premiums were the most important factor in their selection of a qualified health plan (see Figure 10). Another 25 percent identified out-of-pocket payments as most important, with only 22 percent reporting that access to a preferred provider was most important. 100 Marketplace price competition is particularly powerful because premium tax credits are set with reference to the second-lowest cost silver plan available to a consumer. Any amount that a consumer pays for a plan above that benchmark comes directly from the consumer’s pocket.

Narrowing provider networks provides the most common approach used by insurers to lower both premiums and out-of-pocket payments. 101 This appears to be an appealing strategy to many consumers. Fifty-four percent of consumers who report that they had the opportunity to save money by enrolling in a QHP with a narrower provider network chose to do so. 102

Insurers also compete by offering a range of cost-sharing alternatives. Although cost-sharing packages must meet actuarial value standards, there are many different ways in which plans can be designed to meet the same actuarial standard. Different cost-sharing packages may be attractive to different consumer groups. Although, as we noted earlier, high cost-sharing may harm low-income populations, within limits, diversity and choice in cost-sharing alternatives is beneficial to consumers. Competition in this area, however, also imposes significant possibilities for confusion, imposing large responsibilities for processing information on individual consumers.

There is evidence that premiums are lower in marketplaces in which many insurers actively compete. 103 Consumers also presumably benefit from being able to choose from a number of plans that offer different provider networks and cost-sharing packages. The challenge is to improve consumer choice while managing the accompanying cognitive and informational burdens. Experience from Medicare Advantage and other arenas indicate that, absent proper structure and decision supports, offering consumers too many choices can actually impede consumers’ ability to make effective decisions. 104 Important deficits in the information provided to consumers also limit their ability to make optimal plan choices.

In the run-up to the implementation of the ACA, proponents occasionally spoke of the process of buying marketplace coverage as something that could be done with the ease of selecting a book on Amazon.com. That vision was over-optimistic, given the complexity of insurance products. The current consumer experience, in both the state and federal marketplaces, certainly does not approach that standard.

The sheer volume of Americans who have used the marketplace accounts for much of the technical challenge. According to a recent Commonwealth Fund report, 105 one-quarter of all U.S. adults age 19 to 64 have visited the new marketplaces. Fifteen percent of visitors enrolled in Medicaid; 30 percent enrolled in a private plan. Each of these individuals required extensive information processing, linking across multiple federal agencies and qualifying health plans, including identity verification, citizenship checks, and the computation of premium tax credits. These challenges crashed the initial launch of the federal healthcare.gov website and some state marketplace websites. They still affect the consumer experience in many ways.

With due allowance for inherent complexity, the human experience interacting with the new marketplaces remains mediocre. Partly as a result of these shortcomings, consumers often err in choosing marketplace health plans. 106

Survey data collected in 2014–15 by the Commonwealth Fund underscores the challenge. The low response rate (12.8 percent) suggests a need for further investigation regarding consumer experience. Yet the overall pattern is consistent with other data and media accounts. 107 Fifty-eight percent of marketplace visitors rated the experience unfavorably, as either “fair” or “poor.” Forty-seven percent of those who successfully obtained coverage nonetheless rated the experience unfavorably. Among those could not or did not enroll, 54 percent flatly rated the experience as “poor.” 108 In the absence of greater decision supports and transparency, consumers understandably base their plan choices on their monthly premiums or on behavioral inertia, even when such choices provide a demonstrably poor match to their true needs based on predicted out-of-pocket payments, health needs, and other pertinent factors.

Consumers require significant help making sense of complex provider networks; premiums, deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance; and pharmaceutical formularies. 109 These activities must be made easier and more transparent, especially since the mechanics of the process compel consumers to comparison-shop every year. 110 Policymakers must also consider other changes to ensure that plans provide both consumers and regulators with standardized and timely information regarding provider networks, covered medications, and other basic issues.

Improved decision aids could help consumers make better and more informed choices. This is a critical concern to ensure that individuals obtain affordable coverage, and to ensure that marketplace competition disciplines premium increases across plans.

The dynamics of the 2015 open enrollment process underscored the importance of active consumer comparison-shopping. An individual who purchased the cheapest 2014 silver plan and retained it in 2015 would experience an average 8.4 percent premium increase. That same consumer, if she had chosen the cheapest 2015 silver plan, would have experienced only an average 1.0 percent increase. 111

One-third of re-enrolling marketplace participants changed plan metal levels in 2015. The remaining two-thirds of metal plan participants retained their 2014 plan level. Many who remained with their same plans likely over-pay, since switchers saved an average of $400 annually. 112 Comparable data from 2016 plans are now becoming available. These likely will exhibit similar patterns.

Some tools for improving consumer decision-making are emerging in the federal marketplace and across the states. Consumers can obtain much more information and browse available marketplace options as “anonymous” users. This is a major advance over the initial open enrollment, which generally required individuals to establish personally identified marketplace accounts before gaining access to such information.

For the 2016 open enrollment period, healthcare.gov has substantially upgraded shopping tools. Materials recently released by CMS indicate important changes for the current marketplace. These include faster and improved browsing and account management, more user-friendly navigation, and simplified re-enrollment processes with comparisons to other local available plans. A new out-of-pocket cost calculator helps consumers estimate overall costs, beyond the monthly premium. This feature provides further information on premiums, deductibles, and co-pays for each plan, based on different anticipated levels of health care utilization. New doctor and prescription drug lookup features will provide consumers with more readily searchable information about network and prescription-drug coverage in different plans. 113

By 2017, additional data will be incorporated, including plan quality ratings and the results of consumer satisfaction surveys. 114 But much more can be done to simplify consumer choice and to improve the choice architecture facing individuals selecting plans.

A recent paper by economists Ben Handel and Jonathan Kolstad exemplifies how personalized decision supports and defaults could make marketplaces more transparent and competitive, and also less burdensome to individual consumers. 115 A key insight is that useful decision supports should extend beyond the convenient provision of pertinent information to more much active guidance based on specific information regarding patients’ specific preferences and needs.